Shout out to Ash for posting this on his blog as a guest post and enabling it to reach a wide audience. I wanted to post it here too because it’s something I’m proud of.

This essay is my attempt to capture my experience in yeshiva, probably the most formative experience of my youth. The yeshiva is not named and rabbis’ names have been changed as this isn’t a personal critique on one yeshiva or specific rebbeim, but rather my experience in the system. It's a bit long, as I tried to really capture what it was like throughout every grade and how it slowly changed me. I hope you can stay with me until the end. I promise it's worth it.

The Yeshiva wasn't simply the high school I went to. No, The Yeshiva shaped my life since I was a child. Growing up in the kollel houses, owned by the yeshiva and right near the campus, yeshiva was where we went to daven every single day. Yeshiva was where we ran around and played hide and seek. And every one of my friends' father's went to the yeshiva and had learned in the kollel there.

In eighth grade, I learned that you can insert your own personal davening after Elokai Nitzor . Every single day, I davened, "Hashem, please let me get into The Yeshiva. Please, please." I didn't know what day-to-day life looked like in the yeshiva, but I knew it was the best place for me. I was told by everyone that the yeshiva only accepted the best of the best kids. They said that Rav Yaakov, the Menahel, was specifically harsher on kids from the neighborhood and didn't want to accept them unless they were really, really good. Even my older brother, who I looked up to my whole life, was rejected by the principal Rav Yaakov, who deemed his Gemara skills not up to par. With the help of Hashem, I was determined to show Rav Yaakov I was worthy.

That year, I truly applied myself. I learned how to read a Tosafos, a Rashi, and flew to the top of my class. I was mechaven to the Gemara's questions before the Gemara asked them. My rebbi would praise me every time I raised my hand and added something. I'd get Talmud Hachodesh awards and at the end of the year, I got the Keser Torah award. When it came time to apply for mesivtas, The Yeshiva was the only one I applied to. I knew Hashem wouldn't let me down.

Sitting in front of Rav Yaakov for my farher, the admissions interview, I was terrified. His office was a part of the yeshiva I had never explored as a kid, and Rav Yaakov was someone I had never met. He appeared to be a kind man and gently asked me questions on the Gemara. He probed my answers until he was satisfied I understood the sugya. And then he smiled at me and told me to get my father. My father went in to speak to him, and I was terrified. I knew his last conversation with my father had ended with my brother going to another yeshiva. But my father walked out with a smile. I was accepted!

Today, I wish I wasn't.

The Yeshiva was not a normal high school. Well, it wasn't a high school at all. We called it a mesivta or a yeshiva. But the closest it came to be an innocent high school was ninth grade. We were freshies, not taken so seriously, and we were slowly eased into the intense environment. Rabbi Yaffe, our rebbi, was a sweet old man with a very hoarse voice. If this was another yeshiva, everyone would have made a ton of trouble because Rabbi Yaffe didn't have a disciplinary bone in his body. But this was The Yeshiva, a place that selected for only the best boys. None of us made trouble. We paid attention and gave Rabbi Yaffe our respect. We were good, innocent boys, and we revelled in our respect and ernstkeit.

During English, we could let our wild side out. We all knew that we didn't need to respect the teachers like we did the rebbeim. No one cared. It didn't really matter. Even when we were accepted, no one had ever tested us on our English. We only had secular studies because the government mandated it in order for us to get a diploma. We had two and a half hours of secular studies a day. Here, those who were more inclined to make trouble could have fun. Oh, the hijinks I got up to. Climbing out the window in the middle of class, setting Purim shtick on fire on the windowsill, and being a general nuisance to my teachers. I was still a kid, and I felt that way. And my new friends in class acted like kids too, laughing at my immature jokes and pranks on the teachers.

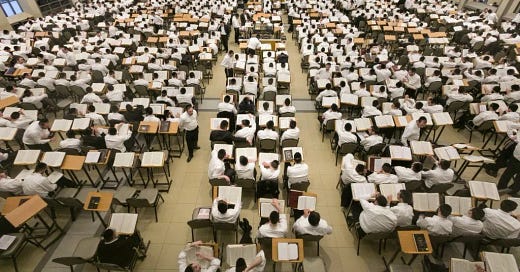

The yeshiva schedule was pretty intense, though. The morning started with shacharis at 7:30 and went until 9:30 when night seder ended. However, we were pretty much off between 3:30 p.m. and 8:00 p.m, when we had English and a break. English was from 3:30 p.m. to 5:50 p.m. and it was mostly a joke. From 5:50 until 8:00 was a break with dinner in between. A lot of boys learned from 7:30 to 8:00 to chazer bekius, as we didn't have a seder for bekius chazara. Their ultimate goal was to learn the whole masechta baal peh.

This brings me to bekius and baal pehs. Another rebbi we had besides Rabbi Yaffe was Rav Chatzkel, who taught us an hour-long bekius shiur. He ran the baal peh program and was the mashgiach. I revered Rav Chatzkel since I was a child. Every Shabbos after davening, everyone lined up to shake the hands of the rabbis and wish them a good Shabbos. Rav Chatzkel was one of the most important rabbanim on that dais. In truth, the Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Sholom, was the real most important rabbi in the yeshiva – the son of a great Gadol of the past generation. However, he was rarely around for Shabbos. Rav Chatzkel was the true head of the yeshiva then. We all worshipped him. Everyone said he was a literal malach. He had an impressive silver beard and walked like he was stepping through the clouds of heaven. In bekios shiur, he demanded respect; we didn't give it to him out of zeeskait. He would never say our names but rather point to you when he called on you. His baal peh program was optional, but would gain you a ton of cred.

At The Yeshiva, you weren't judged by how good you were at basketball (although that helped) or what brand of clothing you wore. No, you were judged by your learning. By your hasmada and your standing in shiur. Baal pehs were a way for a measly freshie like me to gain respect from the whole yeshiva. Everyone who passed the baal peh bechinos and farhers would get their names on the bulletin board in Rav Chatzkel's handwriting, along with their average grade. The higher the grade, the higher your name was on the list. A freshie could get his name on the list right alongside a bochur in third year Beis Medrash if he tried hard enough. This was it. I was determined to show the yeshiva that I was a top bochur alongside the rest of them.

Another area you could gain respect was davening. In ninth grade, I learned a new halacha about davening. You weren't allowed to finish Shemoneh Esrei if the person behind you was still in the middle of his Shemoneh Esrei. Instead, you were forced to stand there awkwardly and uncomfortably, with your feet together, until he's done his Shemoneh Esrei. And people loved their long Shemoneh Esreis in yeshiva. Chazaras hashatz did not start until the biggest rabbi on the dais finished his davening. The only time chazaras hashatz started at a regular time was when Rav Sholom was in, who did a quicker Shemoneh Esrei. I thrived in this new environment. I had a special interest in davening. I bought an interlinear siddur so I could learn what every word meant. I shuckled and shuckled and held every ounce of kavanah I could. Even so, my Shemoneh Esrei wasn't nearly the longest. Some other bochurim went so long that davening could be done for five minutes and they'd still be standing there shuckling. The rest of the bochurim looked on in awe.

Ninth grade was also where I began to be exposed to the values of the yeshiva. These were imparted to me by Rav Yaakov, the menahel, and by older bochurim during mussar seder. Every week, Rav Yaakov would give a shmooze about what we should be doing as Jews. It always boiled down to learning Torah and staying religious. He was very focused on the difference between animals and humans. He had a few stories he loved to repeat. One was about him going to the dentist and asking him if animals got cavities and why they didn't need to brush their teeth. Another was about Rav Shalom Schwadron giving a shmooze and talking about how amazing the life of a cow is. You just sit there and chew your cud, eat grass, and enjoy life. "Rebbi," a bochur asked Rav Schwadron after the shmooze, "I want to be a cow." Rav Schwadron's response? "You are one!" Oh, how Rav Yaakov loved this story. Every bochur in yeshiva knew it. This shmooze was entirely one-sided, though, as no questions or comments were allowed. However, we knew Rav Yaakov knew each one of us because he was the one who accepted us and we knew he was keeping tabs on us. And, if anyone was kicked out of yeshiva, it was Rav Yaakov who would do the honors.

Rav Yaakov would also focus on the obligation to remove ourselves from any outside influence and stay entirely within the realm of the yeshiva. He would constantly rail against the bochurim who went to “Eleven-7” to buy "shlushkies." He'd also knock bochurim who would go to Target and praised those who didn't ever leave the yeshiva, not even to go to the grocery store. The ideal person was the one who remained inside the yeshiva and never left, not for the rest of his life. And we heard stories of great rabbis like this. Gedolim who were so sheltered from outside life, they didn't even know how to work a payphone or go grocery shopping. By Moshiach, at the end of days, we were told, we would all be like this. We would learn and learn, and the goyim would take care of all our physical needs.

This ideal of the sheltered yeshiva bochur who was all Torah played out in real life. To be a good kid, worthy of getting accepted to The Yeshiva, was to be a sheltered kid whose whole life was in the religious world. I was one of the only kids in the yeshiva who had read non-Jewish books like Harry Potter or watched movies at my grandparents' house like Toy Story. Everyone else had no idea, or at least would pretend to have no idea, what these were. Perhaps there were older bochurim who had exposure in their youth, but now no one would be touching "goyish" books and certainly not movies. In fact, if you were caught with a goyish book, you'd be in big trouble. Devices that could play movies were equally forbidden in the yeshiva. Luckily, I lived at home where I could retain access to reading, my favorite hobby.

At The Yeshiva, there was also a culture of spiritual pursuit. We were taught to spurn the material. None of us came from rich homes. We were the type of bochurim that if we found a dollar, we'd post a note on the bulletin board asking who lost it. And people actually did this. There was a certain zeeskait and temimus within everyone.

I had heard that the Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Sholom, was more “normal.” He was a straight shooter who didn't care what was considered "in" in Yeshivish culture. But I didn't encounter him very often. He wasn't around for Shabbos or even much of the weekday. He had his own corner of the yeshiva: the Rosh Yeshiva's office. This was a huge, beautiful room with a big table, and then his office in an adjoining room. There, he would be a choshuv gadol and Rosh Yeshiva. People would come from all over to seek an audience with him. They'd get him to sign documents, endorsing their views, and write haskamos for their books. But us students didn’t see him much. As opposed to Rav Chatzkel or Rav Yaakov’s offices, Rav Sholom didn't have an open office for anyone to knock and enter. He didn't even give a regular Gemara shiur to the top bochurim, like most roshei yeshiva do. The bochurim who did enter that office were either related to him, children of talmidim of his, or very extroverted "macher" type bochurim who pushed their way into a relationship with him.

Once every two weeks or so, we were told that there would be a "va'ad" after Shacharis where Rav Sholom would talk to us. This was the one time we all went into his office and sat at that huge table. There, he'd open a Chumash and start telling us random chiddushim on the Chumash. This wasn't like Rav Yaakov's Mussar Shmoozen where he'd berate us and tell us the right path to be on. Instead, Rav Sholom would tell us his ideas on parshos of Bereishis. This was unusual to us. Bereishis was for kids. Now we were in mesivta; we were supposed to learn Gemara! But these va'adim never changed. They were always ideas on Chumash.

Rav Sholom also spoke like no other rebbe we had. He wouldn't spend his time knocking the outside world or saying how learning is the biggest mitzvah you can do and you must spend your entire life learning and not working. No, he would talk about “God”, a word that we all had thought was assur as it's shem Hashem and you have to say "Hashem" and not God. He'd also occasionally say "Moses" instead of Moshe Rabbeinu! None of us questioned this, though. This was the Rosh Yeshiva Shlitt"a, son of the great Rosh Yeshiva Zatz"al. He was beyond criticism. Years later, however, there were bochurim I knew who would say they didn't hold of the Rosh Yeshiva. They'd point to grandchildren of Rav Sholom who went off the derech, and then point to Rav Yaakov whose grandchildren were all frum. Rav Sholom wasn't Yeshivish enough for them.

And they were right. He wasn't classically yeshivish. I heard that Rav Sholom's wife, the Rebbetzin, would actually go to the library to take out goyish books. I also knew Rav Sholom's grandchildren from the neighborhood, and none of them were that Yeshivish. They read some goyish books and watched some goyish movies like me! But they were like royalty and I never really got to know any of them more. None of them were in my grade and they all went to a "more modern" elementary school than the other kids in the neighborhood.

I wanted to understand Rav Sholom's hashkafa and become more of a talmid, but I never had the chance. As opposed to Rav Yaakov who knew me or Rav Chatzkel who'd have regular sheilos u'teshuvos (Q&A) sessions, Rav Sholom didn't have time for the bochurim. We sat in on his Chumash va'adim, but he never called our names. In fact, I doubt he knew what my name was, despite me being his neighbor my entire life. He definitely never called me by my name, or any of my friends by their names.

Once, Rav Sholom said the name of Jesus in his va'ad. I was shocked. I had never heard a Jew use that name before. I thought it was assur. We called him "Yoshke" or "Yeishu" or even "Cheese and crackers." After the va'ad, I was determined to ask him. But there was never time. The only time people asked him shailos was walking from Shacharis to his car or from his office to his car. People would hang on to him and ask questions. But I felt awkward being in the small crowd of his talmidim, pushing my way to ask him a question. But after the va'ad, there weren't many people escorting him, so I did. And I asked him, "Rebbi, is it muttar to say the name of Yoshke?"

"What? Jesus?" he responded. "Yes, it's muttar. It's his name. Shem Avodah Zara is only assur if it's not the name of a person. But you can say Pharaoh even though he held himself a god, and you can say 'Jesus.'"

And that was it. He gave me his psak. But beyond that, I didn't get anything. I only saw him occasionally. I never understood his hashkafa, of which I heard much from other people, and he never really gave over his values in an accessible forum to us bochurim. He wasn't very impactful on me or the other bochurim.

Instead, I turned to Rav Chatzkel and baal pehs. I knew if I scored high enough, I could get on that bulletin board with the top guys of the yeshiva. I learned and learned and memorized. Instead of spending all my breaks on basketball and hanging out with my new friends, I was in the beis medrash with the shtark guys and the older bochurim learning bekius and chazzering. It was hard but rewarding. Finally, it came time for the farher. I entered Rav Chatzkel's office, where he sat with his long silvery beard.

He opened a huge Gemara to a random page in the perek I studied and started reading. I had to identify which page this was and then continue from where he left off. And I passed with flying colors! I was thrilled. My name would be up there. I was one of the top kids.

Unfortunately, this didn't last. My body and mind rebelled against the idea of sitting in the beis medrash in all my free time. My fourteen-year-old self wanted to play outside and read books and do the things I loved. As much as I pressured myself, it didn't work. My grades began dropping. And while still passing, I would have been towards the bottom of that list on the bulletin board. Finally, around Purim time, I gave up. I thought to myself, well, I'm just a ninth grader. I'll do it next year.

Tenth grade began, and with tenth grade came pressure. It started with Elul shmoozen. Every week, we would get intense speeches about how we're all sinners and we need to repent. "Ellllulllll!!!" they would scream. "Yom Hadin is coming!"I was a good, innocent kid. But that didn't matter. I would be judged for every small sin I did. The rebbeim made it clear that I deserved to die because of all my aveiros. We all deserved to die. But Hashem is kind, and if you cry out and beg him to forgive you, then he won't kill you. As it got closer to Rosh Hashana, we started Selichos. In previous years, I'd go with my father to Manhattan where we would hear the first Selichos from my cousin who was a big chazzan there. It was beautiful. This year, Selichos was more about begging Hashem for forgiveness and not to kill or punish you. And I took it seriously. I begged Hashem for his forgiveness for all my grave sins.

There was nothing like Rosh Hashanah in yeshiva. Every year, the bochurim told me, Rav Chatzkel davened for the amud and cried at a specific spot in davening. They pushed me to stay for Rosh Hashana with everyone else, and I listened. For the first time in my life, I didn't join my parents who went to my grandfather's for Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. No, I stayed in the yeshiva. And I experienced what real davening was. The Yomim Noraim were inspirational but also exhausting. On Rosh Hashana, I went to take a nap during the long day. "You're taking a nap while Hashem is judging you??" I was questioned by my fellow bochurim. They told me I should be learning or davening while the holy tribunal in heaven judged whether I'd stay alive this year or not.

I thought Rosh Hashana was intense, but I wasn't prepared for Yom Kippur. There, we truly begged Hashem to forgive us. We repeated the words of the viduy: confessing our sins. It was strange, though, to say things like "ashamnu, bagadnu, gazalnu": we sinned, we betrayed, we stole. I didn't feel like I did any of those things. But my rebbeim were clear: on some level, I must have done aveiros like that. And we had books like "Pathway to Prayer" that would explain how every sin mentioned relates to something we've probably done. There was perhaps a 45-minute break during the entire Yom Kippur, but the rest of the day was davening. Bochurim would cry, swaying back and forth. I tried to convince myself to cry too, to think about all the sins I did and how I deserved to die and must beg Hashem for forgiveness. I couldn't do it as well as my friends.

Tenth grade is also where I learned the most important sin of all: bittul Torah. I knew already that learning Torah was the greatest mitzvah, how Talmud Torah is k'neged kulam, and therefore every word we say is equivalent to 613 mitzvos. Our rebbeim now taught us that not learning is an equally great sin. Every second you could be learning and you don't, you get the equivalent of every aveirah out there. Our Torah learning wasn’t just a mitzvah but of cosmic importance. We were taught that every second of the day, there had to be someone learning Torah somewhere around the globe. If there wasn’t, the entire world would collapse in on itself. During mussar seder–a time where we all put on our black hats and jackets and studied seforim that were more focused on values and ethics–I studied the Chofetz Chaim's Toras HaBayis with my chavrusa. In it, we learned about the great mitzvos of learning but also about the great aveirahs and punishments you get for time spent not learning.

I took all this extremely seriously. In tenth grade, I worked hard to learn as much as I could. I still had English, a time for me to fool around, but the rest of the time I tried to learn. I was told that time spent not learning could be excused if you had a good reason. You needed an excuse to not learn. For example, you need to eat, or exercise, or have an “outlet.” This is what they called any personal interest you might have: an “outlet.” My time playing basketball was an outlet. My time reading the fantasy books I loved (which really weren’t allowed because they weren’t written by frum novelists) was an outlet. I would learn as much as I can, spending hours of bein hasdarim time learning. And others would do the same. We would peer-pressure each other. From 7:30-8:00, even though it was officially not seder, the basketball court only held ninth graders and a few tenth graders. And these tenth graders were ois vorfs, losers, who weren’t learning during that time. Me? I was in the beis medrash chazzering bekius.

And it worked. Once again I rose to the top of my shiur. When our Gemara shiur was beginning to ramp up in tenth grade to the level of the others and we started learning Rishonim, I understood everything and asked tons of questions. On tests, I’d not only get all the questions right, but I’d also get the extra credit questions correct, scoring a 105 or a 110 along with the top masmidim of my class.

But I still had my outlets, my own time for personal interests. Shabbos was the most important break for me. We had seder for three hours in the afternoon, or at night when it was a short Shabbos, but otherwise I was free. Free to be home for the meals, to read my books, and to relax. I was different. For me, living in the kolel houses, I never had to eat meals at the yeshiva. I was lucky to live so close while all the other bochurim would be stuck in the yeshiva dorms for Shabbos.

They eased you into Shabbos at the yeshiva. For ninth grade, once a month was an “in Shabbos” at the yeshiva. For tenth grade, every other week was an “in Shabbos.” For eleventh grade and up, once a month was an “off Shabbos” but every other Shabbos you were at the yeshiva. But even on “off” shabbosim, I davened and learned at The Yeshiva.

I had another important “outlet” in tenth grade: chess. Besides basketball, this was another game we would play. We played this in the dorms on the top floor of the yeshiva. It was a game my grandfather taught me and one I always loved. I had agreed with a friend of mine, Avigdor, that we would play chess every single day during our 45-minute lunch break until we were the best in the yeshiva. And it worked. We played every single day, and we both got really, really good. We could destroy anyone in the yeshiva in chess, no matter how much of a lamdan they were in learning. We had taught each other the traps and the tricks. Every Friday night, I would show off my skills, challenging anyone in the dorms to a game of chess and usually beating them.

I was so happy. I was excelling in class, known to be the top guy in shiur. I was doing really well on my baal pehs with Rav Chatzkel. I had basketball for exercise where I was decent and my newfound love of chess.

But it was not enough. This perfect balance I had found was not good enough. I was not good enough. My rebbeim made that clear. One Friday night, I was playing chess in the dorms. We were laughing and schmoozing while playing. We were talking about the rebbeim, a typical conversation for us. One said, “Rav Shapiro,” our rebbe, “is so focused on learning that wherever he walks he’s thinking of Torah. He doesn’t spend one second not thinking in Torah. I actually once got a ride with him to Brooklyn, and it was a neis nigleh that we didn’t crash because he was so focused on Torah the whole time. You can tell he’s spaced out.” Another bochur said, “Yes, I heard he once walked into a lamppost and said sorry because he was so focused on learning he thought it was a person.” We would say stories like this about all the rebbeim. How Rav Yaakov could look at a bochur and understand everything about him, and the only reason he does the farher is for show because he knows whether he’ll accept you the first second he looks at you. How Rav Chatzkel was poshut a malach who has never sinned. And how Rav Sholom once saw Eliyahu HaNavi.

I was praising Rav Chatzkel and saying how much of a genius he is when a hush fell over us. I turned to see Rav Chatzkel himself walking towards us. I naively wondered if he knew my name, if he was proud of me, after all the baal pehs I’ve done with him. Rav Chatzkel came to us and gave me a disappointed look.

“Chess?” he asked. “On Shabbos?”

I looked at him confused. Was chess assur on Shabbos? I had never heard that.

“Shabbos is for learning and for getting closer to Hashem,” he clarified. “Not for board games.”

Without even realizing it, I was committing the grave sin of bittul Torah. And on Shabbos, too! I was so disappointed in myself. And told myself I'd never do it again.

Tenth grade is also when we learned about Tochacha, the obligation to tell someone off when they did a sin. If we saw someone doing an aveirah or something not good for his neshama, we had a chiyuv to tell them. If we didn't, then we shared a part of the sin. If we saw another bochur doing something wrong, we should tell them off. If they didn't listen, we should tell a member of the hanhalah. This was for his own good so he wouldn't sink further.

Starting in tenth grade, I would receive explicit pressure from my friends for anything I did that they perceived as “sins.” I had friends who told me off about reading goyish books and others who would try to convince me to sleep in the dorms to be fully enveloped in the holy atmosphere of the yeshiva. I was on the receiving end of snitching– a culture that was prominent in yeshiva, based on this idea of Tochacha.

Music was a great love of mine. I had a tiny iPod nano with all my favorite songs. Of course, they were all Jewish songs. Recently, I had begun putting shiurim on it to listen to, too. Rav Chatzkel called me into his office after Mincha one day. This was the first time I had been there not for a baal peh, and I wondered why. “Do you have a radio?” he asked me. A radio? I was confused. Like the ones they have in cars? I had no idea why he was asking me. “I was told by another bochur that you were listening to the radio.” I realized he was referring to my MP3 player, and I told him that yes, it does have a radio on it, but I never used it. He asked me to get one without a radio. This type of snitching was typical, and while I never snitched myself, I did start giving people tochacha when I saw them doing the wrong thing.

I stayed focused. Despite the snitching and no more chess, I stayed on track. I learned and learned and focused. It wasn’t enough, though. My brain and body couldn’t keep up with the stress and pressure I was putting on it. I started to slip just a little. Instead of staying focused the entire time during seder with my chavrusa, I started to schmooze a little– what was derogatorily referred to as “battel’ing.” My rebbe, Rav Shapiro, called me over. He told me off for wasting time during seder. “But I finished all the chazara already,” I tried to explain. I didn’t have anything left to do. That didn’t matter. That just meant I had more potential. I should be pulling out Rishonim that no one else was learning. I should be moving ahead in leaps and bounds. I needed to fulfill the yeshiva’s dream for me, to become the biggest lamdan and masmid. To eventually, maybe, even become a gadol b’Yisroel.

I was still keeping up academically, but not with the insane grades I had before. My baal pehs were going from the mid-90s to the high 80s. The bechinos I had with Rav Shapiro went from 110s and 105s to 98s and 95s. I was still in the top quadrant of the class but not the very top bachur anymore. Rav Shapiro called me aside again after he gave me the test. “98?” he asked, disappointedly. It was the first time a rebbe had been disappointed in me.

“But it’s a good grade,” I protested.

“Maybe this is a good grade for another bochur, but for you, I expect 105s like your last tests.”

I tried harder. I achieved the level of hasmada that was expected of me for a week or two, but then that would quickly peter out and I went back to where I was. The biggest shock came to me after PTA. I had brought home a report card of 90s and 100s in limudei kodesh. I scored worse in English, but no one really cared about that. My parents were proud of me. But they returned from PTA with dark looks. Rav Shapiro said I wasn’t doing so well. He said that I had been the top bochur but then I stopped trying so hard and would spend seder schmoozing with my friends. I was such a “ba’al kishron.” This was a word that would haunt me. What every rebbi would call me. Someone with a lot of potential. I could be so great. If only I focused. If only I reached the level of hasmada some of the top guys were reaching. I’d be better than all of them with all my kishroinos. The Yeshiva had people learning around the clock. Some older bochurim would learn until 3:30 in the morning and others would wake up at 5:00. That hour and a half in the dead of night was the only time the beis medrash was empty. I had to strive to be like them.

My parents’ looks of disappointment were like a stab in the heart. They had never returned home from PTA looking like this. I told myself I wasn’t doing well enough. I had to try harder. And I did. I tried harder than I ever did before. I stopped reading goyish books or battel’ing. When I was done with what I had to do in seder, I would start learning a new masechta, Brachos, for some extra bekiyus. But it didn’t last. It never lasted. My body and brain begged for me to stop. It begged for the life of a normal 15-year-old. For hobbies and interests. A normal school schedule. It couldn’t handle the constant learning from morning to night. But I didn’t listen. So it rebelled.

Around Purim time, I began getting splitting headaches. These headaches would come randomly and leave me bedridden. My rebbi was upset that I was missing shiur and seder, but I explained that as much as I wished to be there, I had these headaches. “Chash BaRoishoi, Yaasok BaTorah,” Rav Shapiro quoted from the gemara. If one has a headache, learn Torah. But that didn’t work. Part of me was glad for the excuse. With a headache, I couldn’t learn. I was an o'nes. There was nothing I could do about it. I was in yeshiva as much as I could be, but when I got headaches, I was forced to spend my time in bed, reading or listening to music. In bed, I started exploring the radio on my MP3 player that Rav Chatzkel had warned me about. I guiltily listened to non-Jewish music. I disappointed myself. I failed my next baal pehs and fell out of it, losing my chance to make it as one of the top bochurim in yeshiva.

I wasn’t the first to “burn out” in The Yeshiva, nor would I be the last. Throughout my time at yeshiva, I watched friends burn out. They were the top guys in yeshiva when suddenly, one day, they disappeared from the beis medrash. There was Shlomo, in the year above me, who was one of the biggest lamdanim and who took yeshiva extremely seriously, even being among the snitchers. One day, he was just not in yeshiva. Burned out. He returned to yeshiva eight months later with a totally new attitude and became a more chill but weaker bachur. Then there were other kids, like Moshe in my year, who disappeared for months with some sort of “sickness,” like “mono.” He eventually returned to the beis, although not equal to how shtark he was before. (Years later, after I left yeshiva, there was my younger brother who took yeshiva way more seriously than I did and actually was successful in spurning non-Jewish books and learning masechtas ba’al peh. When he eventually ended up in bed, without the energy to go to yeshiva in the morning, I knew what my parents didn’t. He wasn’t suffering from “mono” for months or “post-viral fatigue.” He had “burnout.” Or, more accurately, depression. From all the pressure the yeshiva encouraged him to put on himself. To cheshbon every second in the day whether it was bittul Torah or a justified break and “outlet.”)

Tenth grade ended, and I looked forward to eleventh grade with anticipation for a new start. During our one month of summer vacation, I thankfully was not suffering from headaches. I had decided that I had pushed myself too much and needed to do so less next year. Specifically, I wouldn’t do baal pehs anymore. Instead, I would focus on b’iyun. I could still be a top guy with just b’iyun. Eleventh grade was when we became real yeshiva guys. We had a real schedule of first seder and a lomdish Gemara shiur from Rav Leib, our rebbe. We weren’t full-on yeshiva bochurim yet, as we still had English, our last year with secular studies. However, we were almost there and treated as such.

I entered eleventh grade with a bren, a fire to go back to my rightful place as top bachur. But again, it didn’t last. I loved shiur. I was still the top guy in shiur, asking some of the best questions in class. But seder was hard for me. This was the longest seder I’ve had, around three hours straight, and I just didn’t have the zitzfleish to sit that long and learn. I also didn’t need that much time to prepare. I could do the leining of the necessary Gemara and Rishonim in an hour or two. So I began to schmooze again. And the masmidim in my class would drop me as a chavrusa because they didn’t want to “battel.” People didn’t know what to make of me. I was clearly one of the top lamdanim, but I didn’t have that hasmadah.

I fell into a cycle. Pushing myself to learn and learn and learn. Show up to every seder on time and focus during the whole seder. Ask major questions on my rebbe’s shiur and answer some too. Show up to the beis medrash outside of seder to learn bekius. I was there. But every time, it would peter out. It wouldn’t last, no matter how much I pushed myself. I would then get headaches and fall into a depression. I wasn’t good enough. I couldn’t make it. I’d become a “battlan,” someone who committed the terrible sin of bittul Torah, one of the worst things you can be in yeshiva. Someone who wasn’t in the beis medrash during the whole seder, who wouldn’t show up during bein hasdarim. I’d hang out with the other “battlanim,” guys who struggled just like me. Guys who also secretly listened to goyish songs or kept non-Jewish books under their mattress, far from the eyes of the dorm counselor or the snitchers.

Our rebbe, Rav Leib, was known to be kind of the unofficial therapist of the yeshiva. Even older bochurim would spend hours in one-on-one conversations with him. He had never told me off for the times I didn’t show up to seder, so I decided to go to him for support, unsure how he'd react to my struggles. He listened to me. For the first time in my life at the yeshiva, I experienced real love and warmth. He didn’t talk about how big of a baal kishron I was. He didn’t tell me to continue pushing myself. Instead, he told me to stop putting so much pressure on myself. He told me it was okay to just learn as much as I could, especially with my headaches. He tried to get me to stop. But I didn’t listen, as much as I tried. He was one lonely voice among hundreds who told me the opposite. Everyone else in the yeshiva would judge me when I didn’t show up to seder and would pressure me. The rebbeim, the hanhalah, and especially, the other bochurim. What Rav Leib was saying, to stop pressuring myself and take it easy, made sense, but it didn’t ring true. What about bittul Torah, the greatest sin of all? How could he be correct?

But I tried to listen. I tried to hold onto this small raft of life support he was throwing my way amidst the storm. But the pressure wasn’t the only thing bothering me anymore. I was also questioning my place in the world. I had always expected that I’d lead a life much like my neighbors' parents. I’d go to The Yeshiva, stay there until third year beis medrash, go to Eretz Yisroel for a year or two, come back and go to Lakewood, get married, and learn in Kolel for the rest of my life. But I couldn’t see myself doing that anymore. How would I survive doing this for the rest of my life if I couldn’t even handle the pressure of eleventh grade? I also questioned the point of all this learning. Rav Leib seemed like a safe person, so I had the courage to ask him the question that’s been on my mind for a while. Why?

“Why?” I asked. “Why do we do all this learning?” We were learning about oxes falling into pits, about men dying and their wives marrying their brothers-in-law, about partners that build a wall on their property. The ancient laws and discussions from thousands of years ago. What did all this have to do with Hashem? During b’iyun, we barely mentioned Hashem’s name. How did learning about an ox falling into a pit bring us closer to Hashem, exactly? Don’t get me wrong. I loved it. There was so much intellectual depth. But I loved chess too. How did this work to bring me closer to Hashem? He didn’t scream at me for questioning, as I feared he would, but he didn’t have a good explanation either. There was something magical about learning Gemara b’iyun, he explained. We didn’t understand it, but somehow it brought us closer to Hashem. I told myself that it made sense and I believed him, but in the depth of my heart, I wasn’t 100% convinced.

I tried to stay on the right path, but I wasn’t succeeding. I continued hanging out with the other people who were “up to no good.” We began listening to non-Jewish music together. We talked about movies, and even about girls. We tried to be regular teenagers in this restrictive atmosphere we found ourselves in. But we were all riddled with guilt. Other bochurim would look down at us in disgust when they saw us out of the beis medrash during seder. My chavrusa would go looking for me when I took too long of a break and would tell me off when he found me hanging with “these guys.” I did my best to stop and to only hang out with people who were shtark. I had to spend my time in the beis medrash.

But I craved friendships, and they weren’t in the beis medrash. Boys I was close with in ninth or tenth grade were now no longer around. They had spurned their friendships for learning Torah. When everything is bittul Torah, even hanging out with your friends, you no longer have the time to keep relationships. People would shtark out and disappear from my life, spending all their time learning. I was taught to worship these shtark masmidim, to look up to them, but I also missed them. Boys who were some of my closest friends now didn’t want to talk about anything that wasn’t learning. They wouldn’t even schmooze with me during lunch or dinner. That was bittul Torah. Instead, they pulled out a miniature Gemara or Mishnayos and learned while they ate. Or they wanted to only talk Torah.

Even English was different now. Instead of making trouble, people learned. We had understood that English was bittul Torah and didn’t understand the heter to not learn during this time. Some shtark guys would skip English and learn in the beis medrash, even though they knew the hanhala didn’t approve. Others would bring small Mishnayos or Tanachs to class. I, personally, would try to learn Mishlei during English. One bochur, my chavrusa, even finished the entire Seder Mo’ed during English and made a loud siyum. During the part of the siyum where one says “anu ameilim v’hem ameilim,” he pointed to us and then to our non-Jewish teacher. We all thought it was hilarious. “Anu ameilim l’chayei ha’olam haba (we toil for the world to come),” he said, and we all pointed to ourselves, “v’hem ameilim l’ve’er shachas (they toil for a pit of destruction),” and we all pointed to our teacher and laughed. He had no idea what we were saying.

Eleventh grade was hard, but I survived without a “burnout.” I still had my headaches, but Rav Leib would encourage me not to pressure myself. Whenever I was feeling down, I’d speak to him and he’d help me. The twelfth-grade rebbi though, Rabbi Alpert, was very different. He was known to be an intense man with a thick Boston accent. He had a bit of a cult of personality. People loved him and followed him and would praise him to the moon. “You have to understand Tosafos!” he would shout at us during shiur. His shiur wasn’t a lecture but a back-and-forth with every bochur. Instead of Rav Leib’s majestic blending of different Rishonim and Acharonim, Rabbi Alpert’s shiur was simple and focused on Rashi and Tosafos. He wanted to drill the basics into us.

I started twelfth grade with the same fervor that I had started tenth and eleventh grade. I was determined to show that I could be a top bachur. I wouldn’t hang out with any batlan or leave the beis medrash during seder. This year was the most intense yet. We didn’t have English and had second seder then instead, where we learned a different perek b’iyun. Night seder went late, and the shtark guys would learn even after night seder ended. Throughout the day that began at 7:30 a.m. and ended at 10:15 p.m., we had a 45-minute breakfast break, an hour-and-a-half lunch break, and an hour-and-a-half dinner break. All other times were dedicated to learning. And the good guys had a seder during our breaks too. I kept to this schedule and then some. I learned outside of seder and even had a chavrusa with one of the top guys in the yeshiva, Kalman, before Shacharis. I thrived, and Rabbi Alpert loved me. Until I couldn’t anymore.

A few months in, my body was rebelling. I was getting headaches again. I tried to scale it down, canceling my chavrusas during bein hasdarim and going home immediately after night seder, but it didn’t help. I wasn’t enjoying seder or shiur with Rabbi Alpert anymore. There wasn’t enough for me to prepare in the long seder before shiur when all we focused on was the Tosafos. I loved second seder, but I couldn’t sit for three hours straight with my chavrusa, the top guy in my shiur who wouldn’t allow a single word of battalah. The headaches were coming back.

Rabbi Alpert wouldn’t accept excuses, though. He was similar to Rav Shapiro but even more on top of me. He’d tell me off if he saw me outside the beis during seder. He’d have me sit right next to him if he saw me battel’ing with my chavrusa. He didn’t allow me to take the pressure off but added to it. “Y’udaryeh!” he would scream my name when he saw me spacing out in shiur. “What’s the pshat in Toisfos?!” At his urgings and at my own pressure, I tried again, pulling myself back on that horse, and again I'd fall off. But I kept trying. I’d be amazing for a few weeks and then burn out for a few weeks. The cycle continued until around March time, the long Choref Zman being too much for me. I fell into a deep depression, or a “burnout.” It was my fault I wasn’t doing well in yeshiva. I was a sheigetz, an oisvorf. I was doing major bittul Torah.

I started walking around with my shirt perpetually untucked. I started hanging out at home, secretly watching movies in my parents' basement. I would chill in the dorm rooms of my friends who also struggled. I stopped looking at myself as above them and hanging out with them as a weakness. I learned that one’s parents were getting a divorce, and one had a father who was in a coma. But most of them were like me. They just couldn’t handle this intense yeshiva. They were trying to find some sort of normalcy. Some walked a mile and a half to the public library for escape, wearing a disguise of the only polo shirt they owned and sunglasses so no one from the yeshiva would recognize them. On the long Fridays, we would walk a mile to Target, our one escape with a bit of a window outside our yeshiva world. Some of them secretly bought smartphones there, a means to escape even while in yeshiva. If they were caught, they knew they’d be immediately expelled.

We would hang out on the rooftop, the one place we couldn’t be caught, told off, or snitched on. Going to the roof of the yeshiva was absolutely outlawed, with a fine of $250 if you were caught there. But we were safe there because no rebbi would ever go up there and the good kids who snitched wouldn’t be caught dead up there either. There, we could listen to non-Jewish music or watch movies with impunity. Most of the time I’d spend with them was during first seder or night seder, when we prepared and when we chazzered for shiur. I was so bored of shiur and just did not want to be in the beis medrash. My rebbi, Rabbi Alpert, pushed me harder. He found me a top guy from the shiur above me, Baruch, who could be my chavrusa. He knew that I needed intellectual stimulation. He also made sure I sat right in front of him so he could see if I ever left.

And it worked for a bit. Baruch was really smart, and we delved into the sugyas. However, he also had a body odor issue. He didn’t use deodorant. This was typical in yeshiva. The guys who would do best, who could really spend every second of their day learning, were generally not neurotypical. They had some sort of social issues and thrived in the strict atmosphere and structure of the yeshiva. I loved learning with him, but it was so intense, both the smell and the learning. Rabbi Alpert loved to argue, and he loved to scream while doing it. I sat right next to him and would hear the screaming matches, and Baruch loved participating. This wasn’t for me, my insides shouted. But my brain didn’t listen. They had convinced me I needed to be here. So I tried to be. I told myself I’d stay in this, and I’ll be in The Yeshiva until it was time for me to go to Eretz Yisroel.

I couldn’t wait for this long Choref Zman to end. I just wanted it to be over. Before Bein Hazmanim, bochurim were bragging during dinner about how much they’ll be learning. “I’m having a full morning seder with my father during Bein Hazmanim,” one claimed boastfully.

“Well, I’m having two,” I said sarcastically. “One seder the first night of Pesach, and one the second night.” I was so sick of this atmosphere.

After Pesach, I came back broken. Instead of feeling refreshed from the Pesach break, I had spent it dreading to return. During the new zman, I didn’t care what Rabbi Alpert thought of me anymore. It couldn’t be any worse than what I thought of myself. I started coming late to Shacharis and not showing up to seder. I had bought a cell phone over the Pesach break. A “dumb” phone because my parents had gotten rid of our home phone and I needed something at home. I only used it at home, as it wasn’t allowed in the yeshiva. Rabbi Alpert convinced me to give him the number. He’d leave long voicemails on my answering machine: “Y’udaryeh! You have to come to Shacharis! Where are you?” I ignored them. I’d show up to shiur with clear disinterest. I still couldn’t help myself from keeping up, though. I needed to continue with the minimum, at least. He would call on me unexpectedly during shiur, and in the most bored, drawn-out voice, I’d explain “pshat in toisfos” in exactly the way he wanted. I was still the top guy in shiur, even if I was a batlan.

I spent more and more time with my new friends, secretly watching movies on tiny iPod screens. Reading books, and laughing. We laughed and laughed. Because we all knew, if we didn’t laugh, we’d cry. I fell into a dark depression. I knew I hated this life. I wanted out. But I had no idea where the exit was. This yeshiva was the only thing I knew. I knew of other yeshivas, like Peekskill, South Fallsburg, or Scranton, but I knew those yeshivas were exactly like mine was. I wouldn’t hack it there either. I started to wish I would die. I’d fantasize about getting a terminal illness that would just end me within a few months. I would sit on the rooftop alone and stare down, listening to music. I listened to Taylor Swift, music about love, about romance: romance I didn’t think I’d ever get because girls were assur. Sometimes, on that roof, I’d walk on the ledge. It was a wide ledge, but a ledge nonetheless. I knew if I fell the wrong way, it was over. Finally over. I’d be out of this world and this pressure.

Rabbi Alpert was worried about me. He saw how I wasn’t putting in my all anymore. “Y’udaryeh,” he shouted at me in the packed beis medrash. “You must not go to college! Promise me, Y’udaryeh! Promise me! You cannot go to college, Y’udaryeh!” He looked into my eyes pleadingly, streaks of red running through those old eyes, and held my hands together encapsulated by his. He begged. I didn’t understand where this was coming from. I never planned to go to college. I didn’t even think that was an option. I didn’t know anyone in college. Everyone I knew stayed in yeshiva after twelfth grade and continued with Beis Medrash. I knew from Rav Yaakov’s shmoozen that college wasn’t a good place for a Jew. If I go to college, I’d end up non-religious and marry a goy. There was no way out, I thought. I was stuck in this yeshiva forever.

Rav Leib saved me. I laid out my heart to him, and he really listened. He encouraged me to find another yeshiva. He told me that was the best thing for me. After I talked with my father, he spoke to Rav Yaakov and Rav Chatzkel about it. They encouraged me to go to Ner Yisroel in Baltimore, a more relaxed yeshiva. In The Yeshiva, we called them harries. Not shtark enough. But maybe that was what I needed. Rav Leib wrote me a shining letter of reference. He described me in terms I didn’t believe and would never have described myself in: a lamdan, a yarei Shamayim, a masmid. He was the only one who ever called me those things. I didn’t end up going there, though. Baltimore was too far. I decided on a similar yeshiva in NYC.

I wasn’t happy there either though, finding it to have identical values as The Yeshiva but just less strict and pressuring. Eventually, I decided to leave the yeshiva world entirely. I opted for a different world: Yeshiva University, a world of Modern Orthodoxy. There, they respected both Torah and a secular education. But, I still davened at The Yeshiva every time I went home, and my old rebbeim heard I was planning to attend YU. They tried to convince me not to. “It’s worse than secular college,” they told me. “At least in secular college, you know they’re goyim, so you won’t listen to their hashkafa. At YU, you’ll accept their krum hashkafa!” The only person who actually listened to me and was proud of me was Rav Leib. “There are a lot of big talmidei chachamim at Yeshiva University,” he told me sweetly. “I think you’ll have a lot of hatzlacha there.”

And he was right. For the first time in a long time, I was happy. I went to my first school basketball game. I studied English and wrote, something I had wanted to do my whole life. I could finally focus on both Torah and my own interests. It was amazing. I was able to decide for myself how much Torah I wanted to study, and I didn’t have to worry about others judging me for it. I was on a new path. A path where Gemara wasn’t the only thing in my life, but an aspect of my life. I could be myself and do the things I love while still being religious. I loved my new life.

Despite my thriving there, rebbeim from The Yeshiva would pointedly not ask me about it. I'd see them when I went home for shabbos and they would pretend I wasn't at YU. Rav Chatzkel would ask me about how my older brother was doing at Brisk, my older brother he barely knew, but refused to ask me, his former talmid, how I was doing at YU.

It took me years to stop feeling guilty for every second I didn’t learn. To stop feeling like even learning Tanach or hashkafa was a waste of time and bittul Torah from learning Gemara. I still miss the yeshiva world. I miss the way they spoke and the close community they built. It was my home for most of my life. I miss my home. I wish there had been space for me there. I wish they had tried to carve a space for me within the community instead of trying to carve me into the space they had. They damaged me, and they’ll continue to damage other innocent, bright-eyed kids like me. The features I described above are not unique to The Yeshiva I attended. These are features inherent in every yeshiva. I’ve read memoirs from bochurim who went to European yeshivas in the 1920’s and 30’s like Radin and Slabodka who described similar environments. Yeshivas like Scranton and Peekskill in America, or Ponovezh and Brisk in Israel, function the same way. Even my friends who went to chabad yeshivas describe similar atmospheres. This is not a bug of the system. This is the intended feature and outcome. This is how The Yeshiva became a top yeshiva in America and how they’ll continue to be.

In YU, I heard a quote from Rav Amital, Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Har Etzion, a hesder yeshiva in Israel. Rav Amital had studied in the Chevron Yeshiva, a top yeshiva in Israel. He said, “In Chevron Yeshiva, they kill a hundred bochurim to create a Rosh Yeshiva. In my yeshiva, I kill the Rosh Yeshiva to create a hundred bochurim.” I was one of the 100 bochurim The Yeshiva killed in their making of the next Rosh Yeshiva.

What were your impressions of the RIETS RY and the Limud HaTorah in RIETS?